ترورسفید درتایوان چیان کایچک

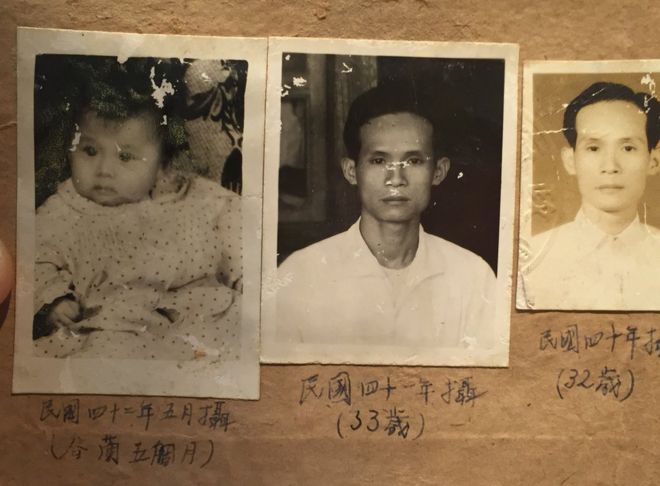

The night before Huang Wen-kung was executed, he wrote five letters to his family, including his five-month-old daughter whom he had never seen.

It was the first and last time he had communicated with her.

“My most beloved Chun-lan, I was arrested when you were still in your mother’s womb,” said the 1953 letter.

“Father and child cannot meet. Alas, there’s nothing more tragic than this in the world.”

His daughter only got the letter 56 years later.

“As soon as I read the first sentence, I cried,” Huang Chun-lan said. “I finally had a connection with my father. I realised not only do I have a father, but this father loved me very much.”

The letters were among some 300 papers handed to Ms Huang’s daughter when she applied for documents about her grandfather from government archives in 2008.

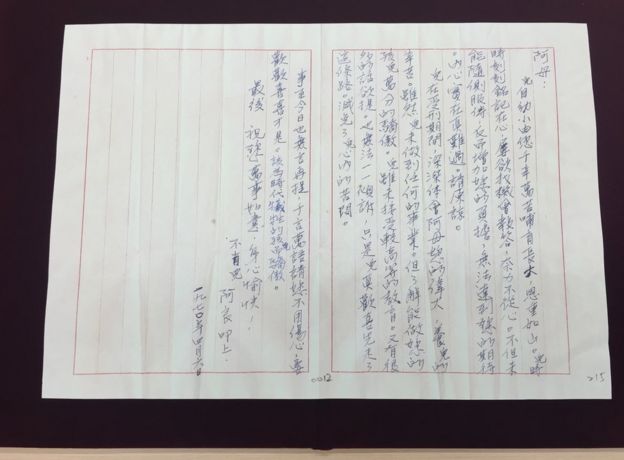

That led to archive workers finding personal writings, mostly letters to families, that another 179 political prisoners had written before they were executed during Taiwan’s “White Terror” period of suppression.

Tens of thousands of people suspected of being anti-government were arrested, and at least 1,200 executed, between 1949 and 1992.

The letters, and the recent election of opposition leader Tsai Ing-wen as president, have renewed calls for a thorough look at this dark period and its precursor, the 228 Incident.

This was a 1947 crackdown on protesters who voiced discontent over the then Kuomintang party’s rule over Taiwan as it faced defeat by the communists in mainland China.

The estimate of the number of civilians killed in the crackdown ranges from 2,000 to more than 25,000 civilians.

Experts say a lot remains unknown about both periods, due to a lack of transparency.

The government never issued a death toll. It is barely mentioned in history textbooks, researchers say.

Historians also say papers may have been destroyed. It was not until 2002 that Taiwan’s Archives Act prohibited important documents from being destroyed.

Taiwan’s president-elect clearly believes that how the country deals with its past will affect its future social and political cohesion.

She indicated recently it still had not properly dealt with this period despite the designation of 28 February as a public holiday to commemorate victims of the 228 Incident, and memorials, compensation payments and presidential apologies.

“Only with truth will there be reconciliation,” she said in a recent speech. “Only with reconciliation will there be unity. Only then can Taiwan move forward.”

She has pledged to seek truth and justice.

Seeking closure

For victims’ families, learning about the fate of their loved ones, while knowing nobody was punished, is difficult to swallow.

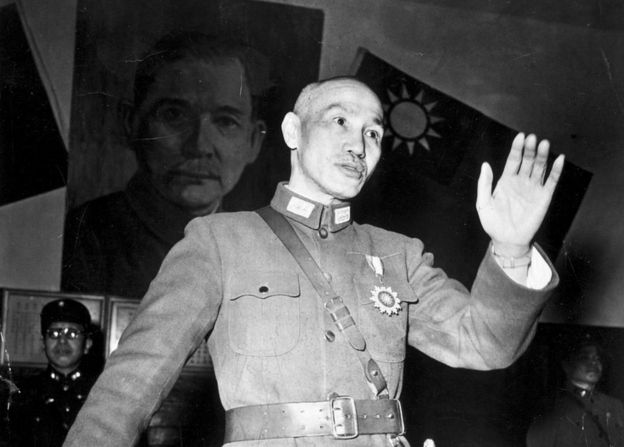

The many memorials to Taiwan’s then President, Chiang Kai-shek, who they see as the biggest culprit, deepen the pain.

Lan Yun-jo, whose father was executed in 1951 for writing articles critical of the government in an underground newspaper, learned only through a researcher that his life might have been spared had it not been for Chiang.

Her father went into hiding and was not arrested despite a big cash reward offered for his whereabouts. He surrendered after the authorities jailed Ms Lan’s mother and Lan, who was a baby then and needed to be breastfed. Within six months, he was executed.

“Under his hands, many jail sentences were converted to death sentences,” said Ms Lan.

Image copyrightHulton Archive/Getty Images

Image copyrightHulton Archive/Getty ImagesWhile victims’ families label Chiang “the murderer”, others, especially those whose families fled with him from communist China, credit him with liberating Taiwan from Japanese colonial rule.

They argue he had to consolidate control over the island and keep it from descending into chaos and falling under communist rule.

But most agree his methods were excessive.

Some of those arrested did support communism but only because they were repulsed by Chiang’s harsh suppression of dissent.

Others were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time and many were intellectuals who just wanted a more democratic society.

The letters expressing love, sadness and regret provide a window into their hearts.

Despite facing death, some stood by their beliefs.

In one letter, a prisoner wrote to his mother: “There is nothing more that can be said about what has happened to me. I only ask that you not be sad, that you live happily, and that you be proud of your child, who is sacrificing for this era.”

For many families, the letters came too late.

In Ms Huang’s father’s letter to her mother, he deeply apologised for making her a widow at a young age and asked her to remarry.

“When we received these letters, my mother was already suffering from dementia, so she couldn’t understand what we were reading to her,” said Ms Huang, who wants more documents to be declassified.

“This is something we really regret. The truth about history should be revealed.”

ارسالی حسین سالاری